- Procedimiento de codecisión

-

Procedimiento de codecisión

El procedimiento de codecisión es el principal proceso legislativo por el que un proyecto de ley puede ser aprobado en la Comunidad Europea, el primero de los tres pilares de la Union Europea. La codecisión proporciona al Parlamento Europeo el poder de aprobar una legislación, con la aprobación conjunta con el Consejo de la Unión Europea, para lo que se requiere la aprobación de un mismo texto por parte de los dos órganos.

Contenido

Otros procedimientos legislativos

Las principales diferencias con los otros procedimientos legislativos de la Union Europea son los siguientes:

- El Procedimiento de cooperación, proporciona al Parlamento Europea, influencia en el proceso legislativo, pero el consejo puede anulara el rechazo del Parlamento a una propuesta, adoptandola por unanimidad.

- El Procedimiento de consulta, en el cual el consejo no está vinculado por la posición del Parlamento o de cualquier otro organo consultivo, pero si obligado a la consulta al Parlamento.

- El Procedimiento de dictamen conforme, es un voto de una única lectura, a favor o en contra (utilizado, principalmente, en la aprobación de tratados internacionales), la decisión parlamentaria del cual no puede ser rebatida por el Consejo.

- El Procedimiento de Lamfalussy, que proporciona al Parlamento voz a nivel ejecutivo, implementando medidas decididas por la a Comisión en base al procedimiento de Comitología, condebida para las medidas referentes a valores, extendiendose posteriormente a todo el sector financiero europeo, siendo ahora parte del Procedimiento Regulador con Control, reformando el procedimiento de comitología.

Procedural summary

Under the codecision procedure, a new legislative proposal is drafted by the European Commission. The proposal then comes before the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers. The two institutions discuss the proposal independently, and each may amend it freely.

In Council, a new proposal is first considered by a working group for that policy area. The conclusion of the working group's discussions is known as the orientation generale, and usually forms the basis of Council's position at the end of the first reading, which is known as the common position.

Meanwhile, Parliament appoints one of its members as 'rapporteur' to steer the proposal through its committee stage. The rapporteur is responsible for incorporating the committee's amendments into the draft proposal, as well as considering the recommendations of the Committee of the Regions and the Economic and Social Committee. The finished report is then voted on in full plenary, where further amendments may be introduced.

In order for the proposal to become law, Council and Parliament must approve each other's amendments and agree upon a final text in identical terms. If the two institutions have agreed on identical amendments after the first reading, the proposal becomes law; this happens from time to time, either where there is a general consensus or where there is great time pressure to adopt the legislation.

Otherwise, there is a second reading in each institution, where each considers the other's amendments. Parliament must conduct its second reading within three months of Council delivering its common position, or else Council's amendments are deemed to have been accepted, though this time period can be extended by Parliament if it chooses to do so.

If the institutions are unable to reach agreement after the second reading, a conciliation committee is set up with an equal number of members from Parliament and Council. The committee attempts to negotiate a compromise text which must then be approved by both institutions in a thirs reading.

Both Parliament and Council have the power to reject a proposal either at second reading or in third reading, causing the proposal to fall. The Commission may also withdraw its proposal at any time.

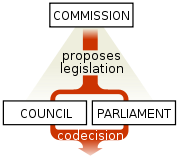

Diagram

For a pictorial representation of the codecision procedure, the EU provides this diagram.

Policy areas where codecision applies

The policy areas where the codecision procedure applies[1] under the current EU treaties are:

- consumer protection

- culture

- customs co-operation

- education

- employment

- equal opportunities and equal treatment

- health

- implementing decisions regarding the European Regional Development Fund

- implementing decisions regarding the European Social Fund

- non-discrimination on the basis of nationality

- preventing and combating fraud

- research

- setting up a data protection advisory body

- social security for migrant workers

- statistics

- the environment

- the fight against social exclusion

- the free movement of workers

- the internal market

- the right of establishment

- the right to move and reside, this including the Schengen rules[2]

The Lisbon Treaty gives the Parliament more power through extended co-decision

- Trans-European Networks

- transparency

- transport

- vocational training

The new Treaty of Lisbon, if it enters into force, will extend codecision to virtually all areas of EU policy.

Development of codecision

The introduction of codecision, under the Treaty of Maastricht, almost completely replaced the cooperation procedure and thereby strengthened Parliament's legislative powers considerably.

Initially, the codecision procedure applied to the following areas of European policy:

- consumer policy

- culture (incentive measures)

- education (incentive measures)

- environment (general action programme)

- free movement of workers

- health (incentive measures)

- research (framework programme)

- right of establishment

- services

- the internal market

- trans-European networks (guidelines)

The Treaty of Amsterdam subsequently simplified the procedure, making it quicker and more transparent, and extending it to more areas of policy.

Most recently, the Treaty of Nice established the codecision procedure for almost any policy area where the Council of Ministers adopts proposals by Qualified Majority Voting (rather than unanimity). The codecision procedure is now by far the most common legislative process in the EU, applying to the vast majority of policy areas.

Criticism

Besides general criticism that the procedure is long and cumbersome, some critics contend that the codecision procedure gives too much power to the Council at the expense of the Parliament. It could be argued that the process is weighted against the Parliament at second reading, as Parliament may only modify or reject amendments from Council by an absolute majority of MEPs, not just those in the chamber at the time.

Defenders reply that the EU is not a full federation and argue that national governments should remain accountable for their collective decisions.

See also

- Cooperation procedure

- Consultation procedure

References

- ↑ How the EU takes decisions

- ↑ «Council Decision of 22 December 2004 providing for certain areas covered by Title IV of Part Three of the Treaty establishing the European Community to be governed by the procedure laid down in Article 251 of that Treaty» (en english) (2004-12-31). Consultado el 2007-11-25..

Enlaces externos

References and official information

- Information from the European Commission:

- Information from the European Parliament:

- Information from the Council:

- The Council's Codecision page which links to its Co-decision Guide (as PDF) it contains a very comprehensive view from the viewpoint of the council

- Information from other institutions:

- Analysis and History:

- Codecision: The recent developments An article from 2000.

- Improving the functioning of the codecision procedure (pdf, doc)

- Formal and Informal Institutions under Codecision: Continuous Constitution Building in Europe

- The extension of the codecision procedure in Amsterdam (PDF)

Other information sources

- The European Parliament (seventh edition, 2007), by Richard Corbett, Francis Jacobs and Michael Shackleton

- Simple top-down diagram of the codecision procedure.

Categoría: Derecho comunitario europeo

Wikimedia foundation. 2010.