- Palacio del Príncipe de Mónaco

-

Palacio del Príncipe de Mónaco

El Palacio del Príncipe de Mónaco, a veces conocido como Palacio Magnífico, es la residencia oficial del Príncipe de Mónaco. Originalmente fundada en 1191 como una fortaleza genovesa, durante su larga y a menudo dramática historia ha sido bombardeada y asediada por varios poderes foráneos. Desde finales del siglo XIII, ha sido la fortaleza de los Grimaldi familia que la capturó en 1297. Los Grimaldi reinaron primeramente el área como señores feudales, y desde el siglo XVII como príncipes soberanos, pero su poder fue a menudo obtenido por frágiles acuerdos con sus más grandes y fuertes vecinos.

Así, mientras los soberanos de Europa iban construyendo modernos y lujuriosos palacios de estilo renacentista y barroco, la política y el sentido común demandaron que el Palacio de Mónaco fuera fortificado. Este único requisito, así como su última fase en la historia, ha hecho del Palacio de Mónaco uno de lo más inusuales de Europa. Irónicamente, cuando sus fortificaciones fueron finalmente terminadas a finales del siglo 18, fue tomado por los franceses, despojado de sus tesoros y cayó en declinación, mientras los Grimaldi se exiliaron durante más de 20 años.

La ocupación de los Grimaldi de su palacio es algo inusual, porque a diferencia de otras casas reales europeas, la falta de palacios alternativos y tomas de tierras resultaron en el uso del mismo palacio por más de siete siglos. Así, sus fortunas y políticas se reflejaron directamente sobre el desarrollo del palacio. Mientras que los Romanovs, borbones, y Habsburgos pudieron, construyeron nuevos palacios, el máximo logro que los Grimaldi pudieron alcanzar cuando gozaban de buena fortuna, o deseos de cambio, fue construir una nueva torre o extremo o, como hicieron frecuentemente, reconstruir una parte existente del palacio. Así, el Palacio del Príncipe de Mónaco no sólo refleja la historia de Mónaco sino también la de una familia que celebró en 1997 sus 700 años de reinado en el mismo palacio.[1]

Durante el siglo XIX y primeros años del XX, el palacio y sus dueños se convirtieron en símbolo de ligereza, glamour y decadencia que fue asociada con Monte Carlo y la Riviera Francesa. Glamour y teatralidad se hicieron realidad cuando la estrella de cine americana Grace Kelly fue nombrada Princesa del palacio en 1956. En el siglo XXI, el palacio sigue siendo la residencia del actual Príncipe de Mónaco.Contenido

Palacio Magnífico

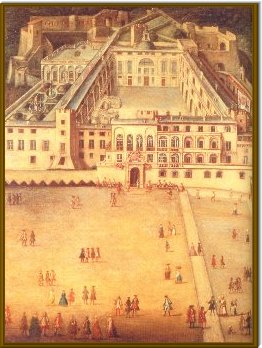

Ilustración 4:En 1890, el palacio del príncipe muestra claramente una mezcla de fachadas clásicas de fortificaciones medievales. Debido al moderno desarrollo de Monte Carlo y el crecimiento de flora esta vista del palacio no es posible hoy en día.

Ilustración 4:En 1890, el palacio del príncipe muestra claramente una mezcla de fachadas clásicas de fortificaciones medievales. Debido al moderno desarrollo de Monte Carlo y el crecimiento de flora esta vista del palacio no es posible hoy en día.

Durante los siguientes cien años, los Grimaldi defendieron su territorio de ataques de otros estados como Génova, Pisa, Venecia, Nápoles, Francia, España, Alemania, Inglaterra y Provenza. La fortaleza fue frecuentemente bombardeada, dañada, y restaurada. Gradualmente los Grimaldi llegaron a hacer una alianza con Francia que fortalecía su posición. Más segura en su posición, los Grimaldi, señores de Mónaco ahora comenzaron a reconocer la necesidad de no sólo defender su territorio sino también de tener un hogar donde reflejar su poder y prestigio.

Así, durante el siglo XV, la fortaleza y la roca fueron ampliados y defendidos hasta que se convirtió en una guarnición para 400 tropas.[2] La lenta transformación de casa fortificada a palacio(Illustration 7) comenzó en esta era, en primer lugar con la construcción por Lamberto Grimaldi, Señor de Mónaco (quien entre 1458 y 1494 fue "un notorio soberano que manejó la diplomacia y la espada con igual talento"[3] ), y luego por su hijo Juan II. Se extendió el lado este de la fortaleza con un ala de tres pisos, guardada por altos muros dentados que conectaban las torres—St Mary (M en la Ilustración 6), Media (K) y Sur(H). Esta nueva ala contenía en principal cuarto del palacio, el Hall de Estado (hoy conocido como el Cuarto de Guardia). Aquí la princesa ejercía sus labores oficiales y presidía la corte.[4] Después completaron cuartos con balcones y loggias que fueron designados para el uso privado de la familia Grimaldi. En 1505 Juan II fue asesinado por su hermano Luciano.[5]

De fortaleza a palacio

Luciano I (1505–1523)

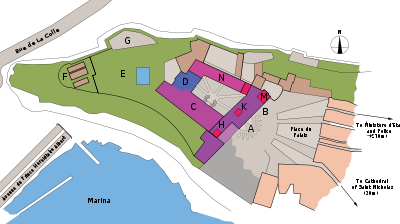

Ilustración 7: El palacio en el siglo 17. El Norte está a la derecha del cuadro. A: Entrada; B, C: Departamentos estatales, doble galería, y escaleras en herradura; D: Futuro sitio de la capilla; E, F: Torre de Todos los Santos; G: Serravalle; H: Torre Sur; K: Torre Media; M: Torre de Santa María.

Ilustración 7: El palacio en el siglo 17. El Norte está a la derecha del cuadro. A: Entrada; B, C: Departamentos estatales, doble galería, y escaleras en herradura; D: Futuro sitio de la capilla; E, F: Torre de Todos los Santos; G: Serravalle; H: Torre Sur; K: Torre Media; M: Torre de Santa María.

Juan II fue sucedido por su hermano Luciano I. La paz no reinó en Mónaco por mucho tiempo; en diciembre de 1506 14.000 tropas genovesas sitiaron Mónaco y su castillo, y durante cinco meses 1.500 monegascos y mercenarios defendieron la Roca antes de lograr la victoria en marzo de 1507. Esto dejó a Luciano I a un paso de un acuerdo diplomático entre Francia y España para así preservar la frágil independencia del diminuto estado que fue realmente sometido a España. Luciano inmediatamente Comenzó la reparación de los daños de la guerra al fortificado palacio que había sido destrozado por el fuerte bombardeo.[6] El ala principal (ver Ilustraciones 3 & 7 - H to M ), construido por el Príncipe Lamberto y extendido durante el reinado de Juan II, el cual añadió una gran ala (H to C) que todavía alberga los departamentos estatales.

Honorato I (1523–1581)

Durante el reinado de Honorato I la transformación interna de fortaleza a palacio fue continuando. El Tratado de Tordesillas al comienzo del mandato de Honorato I clarificó la posición de Mónaco como un protectorado de España, y así más tarde del Emperador del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico Carlos V. Esto proveyó la seguridad que permitió al Señor de Mónaco concentrarse en hacer más confortable su residencia antes que en la constante necesidad de defenderla.

El patio fue reconstruido, el arquitecto Dominique Gallo designing two arcades, stretching between points H and C. The arcades, fronting the earlier wing by Lucien I, each have twelve arches, decorated by white marble balustrading on the upper level. Today the upper arcades are known as the Galerie d'Hercule (gallery of Hercules) because their ceilings were painted with scenes depicting the Labours of Hercules by Orazio de Ferrari during the later reign of Honoré II. These arcades or loggias provide corridors to the state rooms in the south wing (today known as the State Rooms Wings). On the other side of the courtyard a new wing was constructed and the Genoese artist Luca Cambiasi was charged with painting its external walls with frescoes. It is thought that the galleries (B) to the north wing overlooking the harbour were built at this time.[6]

Further enlargements were carried out in order to entertain the Emperor Charles V in 1529, when he stayed four nights at the palace during his journey in state to Bologna for his coronation by Pope Clement VII.

Illustration 8: Prince Honoré II became in 1633 the first prince. He did much to create the palace as it appears today.

Illustration 8: Prince Honoré II became in 1633 the first prince. He did much to create the palace as it appears today.Arquitectónicamente fue un periodo exitante, pero Honorato II fue incapaz de remodelar la fortaleza en el gran estilo Renacentista palazzo. A pesar de la protección española, el riesgo de un ataque francés era alto, y por eso la defensa fue la principal prioridad de Honoré.Con esto en mente, agregó dos nuevas construcciones: La Torre de todos los santos (F) y el Bastión de Serravalle (G). La Torre de todos los santos era semi-circular y estuvo resguardada por un promontorio de roca. Completo con plataformas de armas y cañones, estuvo conectada por cuevas artificiales cavadas en la misma roca. Pasages subterráneos también la conectaron con el Bastión de Serravalle, which was in essence a three-storey gun tower bristling with cannon. Underneath the courtyard a cistern was installed, providing sufficient water for 1000 troops for a 20-month siege, with a huge vaulted ceiling supported by nine columns. Monaco was to remain politically vulnerable for another century and little building work took place from 1581 until 1604, during the reigns of Prince Charles II and Prince Hercule.

Honorato II (1597–1662)

Illustration 9:This painting by Joseph Bresson shows the palace in 1762, viewed from a similar angle as the drawing above. The alterations made by Honoré II are clearly visible, as is the horseshoe staircase of Prince Louis I. The cupola surmounting the new chapel is at the rear of the courtyard.

Illustration 9:This painting by Joseph Bresson shows the palace in 1762, viewed from a similar angle as the drawing above. The alterations made by Honoré II are clearly visible, as is the horseshoe staircase of Prince Louis I. The cupola surmounting the new chapel is at the rear of the courtyard.

Monaco's vulnerability was further brought home in 1605 when the Spanish instaló una guarnición allí. En 1633 Honorato II (Illustration 8), fue oficialmente tratado como "Serene Prince" por Felipe IV de España, así reconociendo a Mónaco como un principado por primera vez. Sin embargo, as Spanish troops were currently in occupation, this recognition was seen as little more than a gesture to keep Honorato happy.[7]

Honorato II fue un francófilo. Following his education in Milán, he had been cultivated by the intellectual salons of Paris.[2] Thus, having close affinities with France both culturally and politically, he rebelled against the Spanish presence in Monaco. While he realised that Monaco needed the protection of another power, France was Honoré II's favoured choice. In 1641, heavily supported by the French, he attacked the Spanish garrison and expelled the Spanish, declaring "the glorious liberty of Monaco".[8] The liberty mentioned was entirely dependent on France, as Monaco now entered a period as a protectorate of France which would last until 1814.[9] As a result of this action Honoré II is today regarded as the hero of Monaco.[8]

Highly educated and a patron of the arts, Honorato II, secure on his throne, began collecting works by Titian, Durero, Raphael, Rubens y Michelangelo which formed the basis of the art collection which furnished the palace slowly evolving from the Monaco fortress. Over the following 30-year period he transformed it into a palace suitable for a prince (Illustration 9).

He commissioned the architect Jacques Catone not only to enlarge the palace, but also to soften its grim fortified appearance. The main façade facing the square, the "front" of the palace, was given decorative embellishments. The upper loggias (B) to the right of the entrance were glazed. Inside the palace the State Rooms Wing was restyled and the enfilade of state apartments created. A new chapel adorned by a cupola (built on the site marked D) was dedicated to St John the Baptist. This new work helped conceal the forbidding Serravalle Bastion from the courtyard, to create the lighter atmosphere of a Renaissance palazzo.

Dueños ausentes y Revolución (1662–1815)

Illustration 11: Antoine Grigho's Baroque entrance to the palace was designed for Louis I.

Illustration 11: Antoine Grigho's Baroque entrance to the palace was designed for Louis I.

Illustration 12: Princess Louise-Hippolyte of Monaco. The palace she barely knew is clearly visible in the background of this painting dated 1712.

Illustration 12: Princess Louise-Hippolyte of Monaco. The palace she barely knew is clearly visible in the background of this painting dated 1712.

Durante the late 17th century and early 18th century, while Monaco was officially an independent state, it was in reality a province of France.[3] Its rulers spent much of their time at the French court, in this way resembling the absentee landlords so prevalent at the time amongst the French aristocracy. The lure of Versailles was greater than that of their own country.

Honorato II fue sucedido por su nieto, el Príncipe Luis I. El nuevo príncipe had an urbane personality and spent much time with his wife at the French court, where he enjoyed the unusual distinction of being both a foreign head of state and a peer of France. Impressed by the palaces of the French king, who had employed the architect Jean du Cerceau to carry out alterations to the palace at Fontainebleau, Louis I used Fontainebleau as the inspiration for enhancements to his palace at Monaco. Thus he was responsible for two of the palace's most notable features: the entrance—a huge Baroque arch surmounted by a broken pediment bearing the Grimaldi Arms (Illustration 11)—and more memorable still, a double horseshoe staircase modelled on that at Fontainebleau (Illustration 10).[10] The thirty steps which compose the staircase are said to have been sculpted from a single block of Carrara marble.[11] Both the architrave of the new entrance and the horseshoe stairs were designed by Antoine Grigho, an architect from Como.[12]

The staircase and entrance, two of the most flamboyant features of the palace were added by Prince Louis. A prince noted for the permissiveness of his private life, his prodigality was notorious. While visiting England in 1677 he incurred the ire of the King Charles II by showering expensive gifts on Hortense Mancini, the king's mistress.[12] The English and Prince Louis later became political enemies when Louis took part in the Anglo-Dutch Wars against England, leading his own Monaco Cavalry into battles in Flandes y el Franco Condado. These acts earned Louis the gratitude of Luis XIV who made him ambassador to the Holy See, charged with securing the Spanish Succession. However, the cost of upholding his position at the papal court caused him to sell most of his grandfather Honorato II's art collection, denuding the palace he had earlier so spectacularly enhanced.[13] Louis died before securing the Spanish throne for France, an act which would have earned the Grimaldi huge rewards. Instead Europe was immediately plunged into turmoil as the War of the Spanish Succession began.

En 1701, Prince Antoine succeeded Luis I and inherited an almost bankrupt Monaco,[3] though he did further embellish the Royal Room. On its ceiling, Gregorio de Ferrari and Alexandre Haffner depicted a figure of Fame surrounded by lunettes illustrating the four seasons. Antoine's marriage to Marie de Lorraine was unhappy and yielded only two daughters.[3] Monaco's constitution confined the throne to members of the Grimaldi family alone, and Antoine was thus keen for his daughter Princess Louise-Hippolyte (Illustration 12) to wed a Grimaldi cousin. However, the state of the Grimaldi fortunes, and the lack of (the politically necessary) approval from King Louis XIV, dictated otherwise. Louise-Hippolyte was married to Jacques de Goyon Matignon, a wealthy aristocrat from Normandy. Louise-Hippolyte succeeded her father as sovereign of Monaco in 1731 but died just months later. The King of France, confirming Monaco's subservient state to France, ignored the protests of other branches of the Grimaldi family, overthrew the Monégasque constitution, and approved the succession of Jacques de Goyon Matignon as Prince Jacques I.[14]

Jacques I assumed the name and arms of the Grimaldi, but the French aristocracy showed scant respect towards the new prince who had risen from their ranks and chose to spend his time absent from Monaco. He died in 1751 and was succeeded by his and Louise-Hippolyte's son Prince Honoré III.[3]

Honorato III married Catherine Brignole[15] in 1757 and later divorced her. Interestingly, before his marriage Honoré III had been conducting an affair with his future mother-in-law.[16] After her divorce Marie Brignole married Louis Joseph de Bourbon, prince de Condé, a member of the fallen French royal house, in 1798.

Ironically, the Grimaldi fortunes were restored when descendants of both Hortense Mancini and Louis I married: Louise d'Aumont Mazarin married Honoré III's son and heir, the future Honoré IV. This marriage in 1776 was extremely advantageous to the Grimaldi, as Louise's ancestress Hortense Mancini had been the heiress of Cardinal Mazarin. Thus Monaco's ruling family acquired all the estates bequeathed by Cardinal Mazarin, including the Duchy of Rethel, and the Principality of Château-Porcien.[13]

Illustration 13: By the end of the 18th century the palace was once again a "splendid place".[17] Honoré II's front created a palace effect by masking the Genoan towers.

Illustration 13: By the end of the 18th century the palace was once again a "splendid place".[17] Honoré II's front created a palace effect by masking the Genoan towers.

Honorato III fue un soldado who fought at both Fontenoy and Raucoux. He was happy to leave Monaco to be governed by others, most notably a former tutor. It was on one of Honoré III's rare visits to the palace in 1767 that illness forced Edward, Duke of York, to land at Monaco. The sick duke was allocated the state bedchamber where he promptly died. Since that date the room has been known as the York Room.

Despite its lack of continuous occupancy, by the final quarter of the 18th century the palace was once again a "splendid place"[17] (Illustration 13). However revolution was afoot, and in the late 1780s Honoré III had to make concessions to his people who had caught the revolutionary fever from their French neighbours. This was only the beginning of the Grimaldi's problems. In 1793 the leaders of the French Revolution annexed Monaco. The prince was imprisoned in France and his property and estates, including the palace, were forfeited to France.

The palace was looted by the prince's subjects,[2] and what remained of the furnishings and art collection was auctioned by the French government.[18] Further humiliations were heaped on both the country and palace. Monaco was renamed Fort d'Hercule and became a canton of France while the palace became a military hospital and poorhouse. In Paris, the prince's daughter-in-law Francoise-Thérèse de Choiseul-Stainville (1766–1794)[19] was executed, one of the last to be guillotined during the Reign of Terror.[20] Honoré III died in 1795 in Paris, where he had spent most of his life, without regaining his throne. -->

Siglo XIX

Recuperación del palacio

Illustration 15: St Mary's Tower (M), reconstruido por Carlos III que se asemeja a una fortaleza medieval. A la derecha está la torre del reloj de Albert I en piedra blanca de La Turbie.

Illustration 15: St Mary's Tower (M), reconstruido por Carlos III que se asemeja a una fortaleza medieval. A la derecha está la torre del reloj de Albert I en piedra blanca de La Turbie.

Illustration 14: Príncipe Honorato V comienza la restauración del palacio después de la Revolución Francesa.

Illustration 14: Príncipe Honorato V comienza la restauración del palacio después de la Revolución Francesa.

Honorato III fue sucedido por su hijo Honorato IV (1758–1819) cuyo matrimonio con Louise d'Aumont Mazarin ha significado mucho para la restauración de la fortuna de los Grimaldi. Mucha de su fortuna fue mermada por las privaciones de la revolución. El 17 de junio de 1814 bajo el Tratado de París, el Principado de Mónaco fue devuelto a Honorato IV.

El tejido del palacio fue totalmente abandonado durante los años en los que los Grimaldi se exiliaron de Mónaco. Tal era el estado de deterioro que parte del ala este tuvo que ser demolido a lo largo del pabellón del baño de Honorato II, que se ubicaba en el sitio ocupado hoy por el Napoleon Museum y el edificio que albergaba los archivos del palacio.

Restauración

Honorato IV murió poco después de que su trono le fuera devuelto, y una restauración estructural del palacio comenzó con Honorato V y fue continuada después de su muerte en 1841 por su hermano, el Príncipe Florestán I de Mónaco. Sin embargo, al tiempo de la ascensión de Florestan, Mónaco estuvo una vez más experimentando tensiones políticas causadas por los problemas financieros resultantes de su posición como un protectorado de Cerdeña, el país al cual había sido cedido por Francia al final de las Guerras napoleónicas. Florestán, excéntrico (había sido un actor profesional), dejó a cargo de Mónaco a su esposa, Maria Caroline Gibert de Lametz. Despite her attempts to rule, her husband's people were once again in revolt. In an attempt to ease the volatile situation Florestan ceded power to his son Charles, but this came too late to appease the Monégasques. Menton y Roquebrune broke away from Monaco, leaving the Grimaldi's already small country hugely diminished—little more than Monte Carlo.

Illustration 16: Prince Charles III completed the restoration of the palace following the French Revolution.

Illustration 16: Prince Charles III completed the restoration of the palace following the French Revolution.

Florestán murió en 1856 y su hijo, Carlos, who had already been ruling what remained of Monaco, succeeded him as Carlos III (Illustration 16). Menton y Roquebrune pasaron a ser oficialmente parte de Francia en 1861, reduciendo el tamaño de Mónaco en un 80%. With time on his hands, Carlos III now devoted his time a completar la restauración de su palacio iniciada por su tío Honorato V. He rebuilt St Mary's Tower (Illustration 15) y restauró completamente la capilla, añadiendo un nuevo altar, and having its vaulted ceiling painted with frescoes, while outside the fachada fue pintada por Jacob Froëschle y Deschler with murals illustrating various heroic deeds performed by the Grimaldi. The Guard Room, the former great hall of the fortress (now known as the State Hall), was transformed by new Renaissance decorations and the addition of a monumental chimneypiece. Carlos III fue también responsable de otro palacio en Monte Carlo, one which would fund his restorations, and turn around his country's faltering economy. This new palace was Charles Garnier's Second Empire casino, finalizado en 1878 (Illustration 17). El primer casino de Mónaco había abierto la década anterior. Through the casino Monaco became self-supporting.[8]

Declive del poder de los Grimaldi

The successive rulers of Monaco tended to live elsewhere and visit their palace only occasionally. Carlos III fue sucedido en 1889 por Alberto I (Illustration 18). Alberto se casó con la hija de un aristócrata escocés. La pareja tuvo un hijo, Luis, antes de divorciarse en 1880. Albert fue un gran científico y fundó el Instituto Oceanográfico en 1906; como pacifista fundó después Instituo Internacional de la Paz en Mónaco. La segunda esposa de Alberto, Alice Heine, hizo mucho para convertir a Monte Carlo en un centro cultural, estableciendo así el ballet y la ópera en la ciudad. Having brought a large dowry en la familia she contemplated turning the casino into a convalescent home for the poor who would benefit from recuperation in warm climes.[21] La pareja se separó antes de que ella pudiese poner en acción sus planes.

Alberto fue sucedido en 1922 por su hijo Luis II. Luis II había sido criado por su madre y su padrastro en Alemania, y no conoció Mónaco hasta la edad de 11 años. Tuvo una relación distante con su padre y sirvió en la Armada Francesa. While posted abroad, él conoció a su amante Marie Juliette Louvet, con quien tuvo una hija, Charlotte Louise Juliette, nacida en Argelia en 1898. Como Príncipe de Mónaco, Luis II spent much time elsewhere, preferiendo vivir en la finca familiar de Le Marchais, cerca de París. En 1911, el Príncipe Luis had a law passed legitimising su hija so that she could inherit the trono, in order to prevent its passing to a distant German branch of the family. The law was challenged and developed into que llegó a conocerse como crisis sucesoria de Mónaco. Finalmente en 1919 el príncipe adoptó formalmente a su hija ilegítima Charlotte, que llegó a ser conocida como Princesa Charlotte, Duquesa de Valentinois. La colección de Luis II collection of artefacts belonging to Napoleón I form the foundation of the Napoleon Museum at the palace, which está abierta al público.

Durante la II Guerra Mundial, Louis attempted to keep Monaco neutral, although his sympathies were with the Vichy French Government.[22] This caused a rift con su nieto Rainiero, his daughter's son, and the heir[23] to Louis' throne, who strongly supported the Allies contra los Nazis.

Following the liberation of Monaco by the Allied forces, the 75-year-old Prince Louis did little for his principality and it began to fall into severe neglect. By 1946 he was spending most of his time in Paris, and on 27 July of that year, he married for the first time. Absent from Monaco during most of the final years of his reign, he and his wife lived on their estate in France. Prince Louis falleció en 1949 y fue sucedido por su nieto, Rainiero III de Mónaco.

Rainiero III

Illustration 19: Sentries and cannon guard the entrance to the restored palace

Illustration 19: Sentries and cannon guard the entrance to the restored palace

El Príncipe Rainiero III fue el responsable for not only turning around the fortune and reputation of Monaco but also for overseeing the restoration and return to glory of the palace. Upon su ascensión al trono en 1949, el Príncipe Rainiero III immediately began a program of renovación y restauración. Many of the external frescoes on the courtyard were restored, while the southern wing, destroyed following the French revolution, was rebuilt. This is the part of the palace where the ruling family have their private apartments.[11] The wing also houses the Napoleon Museum y los archivos.

Los frescos decorating the open arcade known as the Gallery of Hercules were altered by Rainier III, who imported works by Pier Francesco Mazzucchelli depicting mythological and legendary heroes.[11] In addition many of the rooms were refurnished and redecorated.[24] Many of the marble floors have been restored in the staterooms and decorated with intarsia designs which include the double R monogram of Prince Rainier III.[2]

Junto con su mujer, Grace Kelly, El Príncipe Rainiero no sólo restauró el palacio, but from the 1970s also made it the headquarters of a large and thriving business, which encouraged light industry to Monaco, the aim of which was to lessen Monaco's dependence on the income from gambling.[1] This involved land reclamation, el desarrollo de nuevas playas, and high rise luxury housing. As a result of Monaco's increase in prestige, in 1993 it joined the Naciones Unidas, con el heredero de Rainiero, el Príncipe Alberto como cabeza de la delegación de Mónaco.[1]

La Princesa Grace dejó viudo a su marido, falleciendo en 1982 como resultado de un accidente de coche. Cuando Rainierio III murió en 2005 he left both su palacio y su país in a stronger and more stable state of repair financieramente y estructuralmente que había tenido durante siglos.

El palacio en el siglo XXI

Hoy el palacio es hogar del hijo del Príncipe Rainiero y sucesor, Alberto II. Las habitaciones de estado están abiertas al público durante el verano, y desde 1960, el patio del palacio ha sido el lugar donde se han celebrado conciertos al aire libre de la Orquesta Filarmónica de Monte Carlo (anteriormente conocida como Orquesta de la Ópera Nacional).[11]

Notas

- ↑ a b c Monégasques.

- ↑ Error en la cita: El elemento

<ref>no es válido; pues no hay una referencia con texto llamadaPPoM - ↑ a b c d e La casa Grimaldi.

- ↑ Error en la cita: El elemento

<ref>no es válido; pues no hay una referencia con texto llamadaLisimachio_203 - ↑ Los Grimaldis de Monaco sostiene que Juan II fue asesinado por su hermano, mientras que Lucien afirma en The History of Monaco to 1949 que la causa de su muerte fue debido a una pelea que terminó con resultados accidentalmente drásticos.

- ↑ a b Lisimachio p. 204.

- ↑ The Grimaldis of Monaco states the title was recognized to keep the prince happy, but erroneously cites the date of Spain recognizing the title as 1612. While Honorato II had in fact referred to himself as a prince in documents dating from 1612 and 1619, Spain did not officially acknowledge el título hasta 1633 (see Monaco: Early History). The official site The Prince's Palace, Monaco also makes a mistake on this matter, stating "Finalmente en 1480 Luciano Grimaldi persuadió al rey Carlos de Francia y al Duque de Saboya a reconocer la independencia de Mónaco". This is clearly wrong as in 1480 not only was Luis XI el Rey de Francia pero Mónaco fue reinado por Lamberto Grimaldi.

- ↑ a b c The Grimaldis of Monaco.

- ↑ Monaco, 'French Protectorate (1641–93)' and 'Annexation (1793–1814)'.

- ↑ de Chimay p. 77.

- ↑ a b c d Principauté de Monaco.

- ↑ a b de Chimay p. 210.

- ↑ a b Monaco: 1662 to 1815.

- ↑ Archbishop Honoré-François Grimaldi, brother of Prince Louis I, was as a celibate priest not considered as a sovereign. His death in 1748 brought to a close the Monaco branch of the Grimaldi family.

- ↑ Sometimes known as Catherine Brignole

- ↑ Marie Catherine Brignole

- ↑ a b Lisimachio p. 210.

- ↑ Lisimachio p. 211

- ↑ The daughter of Jacques Philippe de Choiseul, comte de Stainville, a Marshal of France, and Thomase Therese de Clermont d'Amboise, she had married Joseph Grimaldi 6 April 1782. (ThePeerage.com).

- ↑ She shared the tumbrel with Andre Chenier. The History of Monaco to 1949.

- ↑ de Fontenoy, p. 87.

- ↑ The Royal Scribe notes that Anne Edwards wrote in The Grimaldis of Monaco that he had collaborated with the Nazis.

- ↑ Princess Charlotte cedió su derecho de sucesión a su hijo, Rainiero, in 1944.

- ↑ Lisimachio.

Referencias

- Lisimachio, Albert (1969). Great Palaces (The Royal Palace, Monaco. Páginas 203–211). London: Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. ISBN 0600 01682 X.

- de Chimay, Jacqueline (1969). Great Palaces (Fontainebleau. Páginas 67–77). London: Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. ISBN 0600 01682 X.

- Edwards, Anne (1992). The Grimaldis of Monaco. William Morrow & Co. ISBN 978-0-688-08837-8.

- de Fontenoy, Marquise (1892). Revelation of High Life Within Royal Palaces. The Private Life of Emperors, Kings, Queens, Princes and Princesses. Written From a Personal Knowledge of Scenes Behind the Thrones. Philadelphia: Hubbard Publishing Co.

- The Prince's Palace of Monaco published by Palais Princier de Monaco. Retrieved 6 de febrero de 2007

- The Grimaldis of Monaco published by Worldroots.com. Written by Phyllida Hart-Davis, St. Martin's Press, New York. Retrieved 6 de febrero de 2007

- Monte Carlo. Société des Bains de Mer published by Société des Bains de Mer. 2006. Retrieved 7 de febrero de 2007

- The House of Grimaldi published by Grimaldi.Org. 1999. Retrieved 7 de febrero de 2007

- Louise d'Aumont Mazarin published by Find A Grave, Inc. Retrieved 8 de febrero de 2007

- Monaco: Early History escrito y publicado por François Velde. 2006. Retrieved 9 de febrero de 2007

- Monaco: 1662 to 1815 retrieved 8 de febrero de 2007

- The History of Monaco to 1949 publicado por GALE FORCE de Mónaco. Retrieved 9 de febrero de 2007

- The Royal Scribe escrito y publicado por Geraldine Voost. Retrieved 15 de febrero de 2007

- Principauté de Monaco publicado por el Ministerio de Estado, Ministère d'Etat, Mónaco. Retrieved 25 de febrero de 2007

- Marie Catherine Brignole published by Worldroots.com. Retrieved 15 de febrero de 2007

- Monégasques publicado por Advameg Inc. Retrieved 6 de noviembre de 2007

Categorías: Palacios de Mónaco | Cultura de Mónaco | Arquitectura románica

Wikimedia foundation. 2010.