- Río Wolf (Tennessee)

-

El río Wolf (en inglés: Wolf River) es un pequeño río sedimentario en el oeste de Tennessee y el norte de Misisipi, cuya afluencia con el río Mississippi ha sido cuna de varias comunidades y fuertes chickasaw, francesas, españolas que posteriormente se han convertido en Memphis.

Contenido

Hidrografía

El río Wolf crece en el Bosque de Holly Springs National Forest (Holly Springs National Forest) at Baker's Pond en el condado de Benton, Mississippi, al norte de Ashland, y fluye al sudoeste hasta Tennessee, cruzando una gran parte de Memphis y el norte y este del condado de Shelby, antes de desembocar en el río Mississippi cerca del norte de Mud Island, al norte del corazón de Memphis.

Poblaciones

- listadas en orden desde el origen hasta la desembocadura

- Ashland, Mississippi

- Canaan, Mississippi

- Michigan City, Mississippi

- La Grange, Tennessee

- Moscow, Tennessee

- Rossville, Tennessee

- Piperton, Tennessee

- Collierville, Tennessee

- Germantown, Tennessee

- Bartlett, Tennessee

- Raleigh, un antiguo asentamiento del condado de Shelby (Tennessee), incorporado desde hace tiempo a Memphis.

- Memphis, Tennessee

Fauna y flora

El área del río Wolf es hogar de cérvidos, nutrias, visones, gatos monteses, zorros, coyotes, pavos y una gran variedad de aves acuáticas. También se han observado migraciones de águilas pescadoras, garzas blancas y águilas calvas a lo largo de este río. There are Tennessee state record trees located in its bottomland forests, including a Tupelo Gum that is 17 pies (5,1816 m) in circumference. Other hardwoods include green ash, red maple, swamp chestnut oak, blackgum, and the majestic bald cypress. Native flowering plants include cardinal flower, ironweed, swamp iris, false loosestrife, spatterdock, swamp rose, blue phlox and spring cress.

Twenty-five species of freshwater mussels (unionidae) have been documented. Their dependence on good water quality makes them vulnerable to pollution.

A growing number of these species of plants and animals can be found in the urban reaches of the Wolf in Memphis, as the legacy of community action and the Clean Water Act slowly heals the degraded downstream section.

Historia

Se estima que el río Wolf tiene alrededor de 12.000 años. Se formó por el corrimiento del Glaciar del Medio Oeste, que dio lugar al blando suelo aluvial de la región. El río Wolf es uno de los muchos ríos en el oeste de Tennesse y Mississippi que motivaron a los Chickasaw a llamar la región "la tierra que pierde" (literalmente: gotear, perder, dejar pasar el agua).

Around 400 CE, a massive seismic event in the Ellendale Fault (part of the New Madrid Fault system) raised a low ridge across present-day east Memphis, diverting Nonconnah Creek away from the Wolf, causing it to flow directly into the Mississippi River several miles south of the Wolf's mouth. The lowermost section of the Nonconnah that continued to flow into the Wolf eventually became known as Cypress Creek.

The Mississippian culture thrived in this area until about the 16th century, as evidenced by mound sites and accounts by Hernando de Soto. Shortly after that, the Chickasaw nation settled northern Mississippi, western Tennessee, and eastern Arkansas.

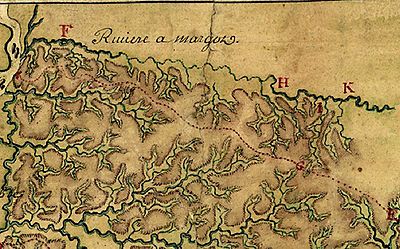

In 1682, French explorer Robert Cavelier de La Salle claimed the region near the mouth of the Wolf River. The French alternately called the river Riviere de Mayot (or Margot), Blackbird River, and Riviere de Loup. The original Loup was rumored to be a Lenape Indian guide who disappeared along the river while guiding the French. The Delawares were also known as Les Loups or "The Wolves." According to one account, both the English and Chickasaw afterwards called the river "Loup" in their respective languages: "Wolf" and "Nashoba." During a multi-river voyage from Chicago, Illinois, to Biloxi, Mississippi, Jesuit priest Jacques Gravier made the following journal entry for 26 October, 1700, after reaching the mouth of the Wolf:

- "We passed the Riviere a Mayot [Wolf] on the south, from the name of a savage of the Delaware nation who was of Mr. de la Salle's party. This river does not seem to be very large, but is said to be a good hunting ground, and that the Chickacha come to its mouth, from which they are only three days‚ journey, cutting south inland."

Concerned about American activities in their territory along the east bank of the Mississippi River, the Spanish colonial government erected Fort San Fernando de las Barrancas in 1795 near the Chickasaw Bluffs at the mouth of the Wolf River. The fort was dismantled in 1797 in accordance with Pinckney's Treaty.

In the early 19th century, the Wolf River was declared navigable, from Memphis to La Grange, by the Tennessee General Assembly, which appropriated funds to remove obstructions for keel boat travel. In 1888, Memphis stopped using Wolf River as its principal source of drinking water, switching to artesian wells, which are still used and which are recharged by the Wolf's watershed.

Because of its foul odor, the Wolf was dammed in 1960 near its mouth and diverted into the Mississippi north of Mud Island. The section of the Wolf downstream of this channel diversion became a slackwater harbor of the Mississippi known today as Wolf River Harbor, which separates Mud Island (actually a peninsula) from the Memphis "mainland." Completion of channelization of the Wolf from the Mississippi upstream to Gray's Creek, east of Germantown, Tennessee resulted in a lowered riverbed and diminished wetland habitat. In 1970, surface drainage, sewage, and industrial pollution caused a group of scientists and environmentalists to pronounce the river "dead" around Memphis.

In 1977 Mary Winslow Chapman published I Remember Raleigh, which including vivid descriptions of a pre-channelized Wolf River.

To form any picture of [the river's environs] we must forget what we now see and imagine the Wolf as it was then, a clear, spring-fed stream slipping silently along through the endless forest, where the unbroken shade shielded it from the fierce Southern sunshine and kept it flowing fresh and cool all summer long...The water was fresh and sweet, flowing out of the uncontaminated woods, but gradually this condition changed. As more and more land upstream was cultivated, more silt was washed into the river. After each rain it took longer for the stream to clear, and finally, with the establishment of the Penal Farm [today’s Shelby Farms] with all its disagreeable effluvia, swimming became impossible...

Gone now forever from this spot are the cane brake and the horses; the tall timber and the mysterious river, where hard by, on Austin Peay Bridge auto traffic streams triumphant, night and day in one unceasing roar, all oblivious of the life and history buried down below.[1]In 1985, the Wolf River Conservancy was founded by an alliance of conservation-minded real estate executives and local environmental advocates. In 1995 the "Ghost River" section of the Wolf was saved from timber auction by a coordinated effort of the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, local conservation activists Lucius Burch and W.S. "Babe" Howard, and the Wolf River Conservancy. In 1997 the river was designated an American Heritage River by presidential proclamation under a special EPA program. In 2005 the Wolf River Restoration Project was commenced by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Memphis Office to stop rapid erosion known as "headcutting" at Collierville, Tennessee.

On the evening of May 29, 1997, Jeff Buckley's band flew in intending to join him in his Memphis studio to work on the newly written material. That same evening, Buckley went swimming in Wolf River Harbor,[102] a slackwater channel of the Mississippi River, while wearing boots, all of his clothing, and singing the chorus of the song "Whole Lotta Love" by Led Zeppelin.[103] Buckley had gone swimming there several times before.[104] A roadie of Buckley's band, Keith Foti, remained ashore. After moving a radio and guitar out of reach of the wake from a passing tugboat, Foti looked up to see that Buckley had vanished. Despite a determined rescue effort that night, Buckley remained missing. On June 4, his body was spotted by a tourist on a riverboat and was brought ashore.[103]

In 2007 the "Middle Wolf" Campaign attempted sprawl-proofing of the western Fayette County section. Completion of the Collierville-Arlington Parkway segment of Tenn-385 and I-269 outer loop expressway, including two (and potentially five) interchanges poised to become major drivers of suburban growth into forested sections of the Wolf River's floodplain and the surface-exposed sections of the Memphis Sands aquifer.

Bottomland hardwood swamp at the confluence of Tubby Creek and the Wolf River in the Holly Springs National Forest near Ashland, Mississippi. This location was considered to be the Wolf's head of navigation at the time of the first known full descent of the river, completed in 1998 by members of the Wolf River Conservancy who hiked or waded from the river's source at Baker's Pond to this point and traveled by canoe to the river's confluence with the Mississippi River.

Bottomland hardwood swamp at the confluence of Tubby Creek and the Wolf River in the Holly Springs National Forest near Ashland, Mississippi. This location was considered to be the Wolf's head of navigation at the time of the first known full descent of the river, completed in 1998 by members of the Wolf River Conservancy who hiked or waded from the river's source at Baker's Pond to this point and traveled by canoe to the river's confluence with the Mississippi River.

Beneficios públicos reconocidos

Según la Wolf River Conservancy (Organización por la Conservación del Río Wolf), el río Wolf beneficia al Centro-sur de Estados Unidos de cuatro formas diferentes:

- Control de la erosión e inundaciones: Durante lluvias fuertes, la planicie aluvial (en inglés: floodplain) y los humedales (en inglés: wetland) del río Wolf contienen temporalmente las crecidas. Cuando éstos se llenan por el desarrollo, el río pierde estas válvulas naturales, causando incrementos en la velocidad del río y el caudal de la riada. Sin la planicie aluvial adecuada, las inundaciones y la erosión amenazan las propiedades, los transportes y las vidas.

- Calidad del agua: El área metropolitana de Memphis y otras comunidades del centro-sur reciben agua potable de un acuífero subterráneo puro bajo la Cuenca del Río Wolf. Los humedales del Río Wolf contienen el agua el suficiente tiempo como para que sea absorbida por el terreno y sirven como filtro natural para purificar el agua contaminada antes de que ésta alcance el acuífero.

- Hábitat salvaje: The Wolf River supports a variety of animals and waterfowl. Migrating osprey, great egret, and bald eagle have been spotted along the river as well.

- Recreo de bajo impacto: Mientras que la civilización siempre ha rodeado la planicie aluvial del Río Wolf, la huella de sus humedales y tierras bajas proporcionan a los habitantes del centro-sur una experiencia escénica de vivencia salvaje desde el Holly Springs National Fores hasta Memphis. Excursionistas, corredores, ciclistas, palistas y otros deportistas experimentan la naturaleza en el río o cerca de él cada día.

Referencias

- ↑ M. Winslow Chapman, I Remember Raleigh, 1977, Riverside Press, Memphis. Excerpts are displayed here with permission of the author's estate.

Véase también

- Lista de ríos de Mississippi

- Lista de ríos de Tennessee

Categorías:- Wikipedia:Traducciones en desarrollo en inglés

- Ríos de Misisipi

- Ríos de Tennessee

Wikimedia foundation. 2010.