- Guerra serbo-búlgara

-

- Este artículo fue creado a partir de la traducción del artículo Serbo-bulgarian War de la Wikipedia en inglés, bajo licencia Creative Commons Atribución Compartir Igual 3.0 y GFDL.

Guerra Serbo-búlgara

Los búlgaros cruzan la frontera, por Antoni PiotrowskiFecha 14-28 de noviembre 1885 Lugar frontera entre Serbia y Bulgaria Resultado Decisiva victoria búlgara;

Reconocimiento de la Unificación de BulgariaBeligerantes  Principado de Bulgaria

Principado de Bulgaria Reino de Serbia

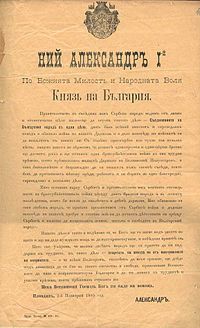

Reino de SerbiaFuerzas en combate 35.000 frente a los serbios en el inicio de la batalla de Slivnitsa; 60.000 al final de al guerra 60.000 Bajas 771 muertos y 4.232 heridos 746 muertos y 4.570 heridos  Manifesto de Knyaz Alejandro I declara la guerra a Serbia

Manifesto de Knyaz Alejandro I declara la guerra a Serbia

La Guerra Serbo-Búlgara (en búlgaro: Сръбско-българска война, translit. Srabsko-balgarska voyna; en serbio: Српско-бугарски рат/ Srpsko-bugarski rat) fue una guerra entre Serbia y Bulgaria que se inició el 14 noviembre de 1885 y duró hasta el 28 de noviembre del mismo año. La paz final fue firmada el 19 de febrero de 1886 en Bucarest. Como resultado de la guerra, las potencias europeas reconocieron en el acto La unificación de Bulgaria, que ocurrió el 6 de septiembre 1885.

Contenido

Antecedentes

El 6 Septiembre 1885, el Principado de Bulgaria y la provincia semi-autónoma otomana de Rumelia Oriental declararon su unificación para formar Bulgaria en la ciudad de Plovdiv. Rumelia Oriental, cuya población era predominantemente de etnia búlgara, había sido creada artificialmente en el Congreso de Berlín siete años antes. La unificación se llevó a cabo contra la voluntad de las Grandes Potencias, incluyendo Rusia. El Imperio Austrohúngaro que había extendido su influencia en los Balcanes se opuso especialmente. El vecino oriental de Bulgaria, Serbia, también se opuso temiendo que esto disminuyera su posición en los Balcanes. Además, el gobernante serbio Milan I le molesto que líderes opositores serbios como Nikola Pašić, que había escapado después de la Rebelión de Timok, habían encontrado asilo en Bulgaria.

Atraído por las promesas de Austria-Húngría de obtener ganancias territoriales de Bulgaria (a cambio de concesiones en los Balcanes occidentales), Milan I declaró la guerra a Bulgaria el 14 Noviembre de 1885. La estrategia militar se basó en gran medida en la sorpresa, ya que Bulgaria había movido gran parte de sus tropas cerca de la frontera del Imperio Otomano, en el suroeste.

El pretexto fue una pequeña disputa fronteriza, conocida como la Disputa del Bregovo. El río Timok, que formaba parte de la frontera entre los dos países, había cambiado ligeramente a lo largo de los años. Como resultado, una casa de vigilancia fronteriza serbia se encontraba cerca del pueblo de Bregovo ubicado en la orilla búlgara del río. Después de varias solicitudes denegadas por Bulgaria para evacuar la casa de vigilancia, Bulgaria expulsó a las tropas serbias por la fuerza.

Como ocurrió, los otomanos no intervinieron y el ejército serbio fue detenido después de la batalla de Slivnitsa. El cuerpo principal del ejército búlgaro viajó desde la frontera otomana, en el suroeste hasta la frontera serbia en el noreste para la defensa de Sofía. Después de las batallas defensivas de Slivnitsa y Vidin (la defensa de ésta última fue organizada por Atanas Uzunov), Bulgaria inició una ofensiva que tomó la ciudad de Pirot. Llegado este punto, el Imperio Austro-húngaro di un paso diplomático ofensivo, amenazando con unirse a Serbia si las tropas búlgaras no se retiraban. Tras la paz no hubo cambios territoriales, pero la unificación búlgara fue reconocida por las Grandes Potencias. Sin embargo, las relaciones de confianza y amistad entre Serbia y Bulgaria, construidas en común durante su lucha contra el poder otomano, sufrió un daño irreparables.

Serbian army

The total number of Serbian armed forces expected to take part in the military operation was about 60,000. The Serbian army's infantry weaponry stood up to the most modern standards of the time (Mauser-Milovanovich single-shot rifles with excellent ballistic characteristics). However, the artillery was ill-equipped, having muzzle-loading cannons of La Hitte system. King Milan IV divided his force into two armies, the Nishava and Timok armies. The first took the main objective, i.e. to overcome the Bulgarian defences along the west border, to conquer Sofia and advance towards the Ihtiman heights. It was there that the army was supposed to encounter and crush the Bulgarian forces coming from the southeast. Serbia's main advantages on paper were the better small arms and the highly educated commanders and soldiers, who had gained a serious amount of experience from the last two wars against the Ottoman Empire.

However, internal Serbian problems supplemented by king Milan's conduct of the war, nullified most of these advantages:

In order to collect all the glory for the victory he considered imminent, King Milan did not call the most famous commanders of the previous wars (Gen. Jovan Belimarković, Gen. Đura Horvatović and Gen. Milojko Lešjanin) to command the army. Instead, he took the position of army commander himself and gave the divisional commands to less experienced officers like Petar Topalović of the Morava division.

Furthermore, underestimating the Bulgarian military strength and fearing mutinies for conducting such an unpopular war (and having indeed experienced the Timok Rebellion two years before), he ordered the mobilisation of only the first class of infantry (recruits younger than 30 years), which meant mobilising only about half of the available Serbian manpower. In doing so, he deprived the Serbian army of its veterans of the previous wars against the Ottoman Empire.

The timing for the beginning of the hostilities was very bad for the Serbian Army as it was in the middle of rearmament with modern weapons. The new De Bange steel, breech-loading cannons were ordered and paid for, but did not arrive until 1886.

The modern rifles, even though amongst the best in Europe at the time, still had issues of their own: they were introduced a rather short time (two years) before the outbreak of the war, so many of the soldiers were not very well trained to use them. More importantly, the theoretical capabilities of the rifle often mislead the Serbian officers, still lacking experience with it, to order volleys from distances of half a mile or more, wasting the precious ammunition for negligible results. Furthermore, the ammunition was purchased in quantities based on consumption of bullets by the previous, much older and slower firing rifles. The situation was made worse still by the contemporary Serbian tactics emphasizing firepower, and downplaying hand-to-hand fighting, which contributed to heavy casualties in such a fight for Neškov Vis in defence of Pirot.

Condition of the Bulgarian Army

Bulgaria was forced to meet the Serbian threat with two serious disadvantages. First, when the Unification had been declared, Russia had withdrawn its military officers, who had until that moment commanded all larger units of Bulgaria's young army. The remaining Bulgarian officers had lower ranks and no experience in commanding units larger than platoons (causing the conflict to be dubbed "The War of the Captains"). Second, since the Bulgarian government had expected an attack from Turkey, the main forces of the Bulgarian Army were situated along the southeastern border. In the conditions of 1885 Bulgaria, their redeployment across the country would take at least 5-6 days.

Bulgarian advantages

The main Bulgarian advantage was the strong patriotic spirit and morale, as well as the feeling among the men that they were fighting for a just cause. The same could not be said about the Serbs. Their King had misled them in his manifest to the army, telling the Serbian soldiers that they were being sent to help the Bulgarians in their war against Turkey. This was why the Serbian soldiers were initially surprised to find that they were fighting Bulgarians instead, until they understood what was happening. Presumably, lying to his army was King Milan's only means to mobilize and command his troops without experiencing disobedience and unrest.

Furthermore, while Bulgarian small arms were inferior to the Serbian, its artillery was greatly superior, boasting steel, Krupp-designed breech-loading cannons.

Bulgarian strategic plan

There were two views on the Bulgarian strategy: the first, supported by Knyaz Alexander I, saw the general battle on the Ihtiman heights. The drawback of this plan was that in that case, the capital Sofia had to be surrendered without battle. This could very well cause Serbia to stop the war and call in the arbitrage of the Great Powers. For this reason, the strategic plan that was finally selected by the Bulgarian command expected the main clash to be in the area of Slivnitsa. Captain Olimpi Panov had an important role in this final decision.

Campañas militares

Véase también: Batalla de Slivnitsa16-19 noviembre

El príncipe Alejandro I llegó en la noche del 16 de noviembre y encontró una posición bien preparada para la defensa por 9 batallones, más 2.000 voluntarios y 32 cañones, comandada por el Mayor Guchev. La posición consistía en cerca de 4 km de trincheras y reductos de artillería a ambos lados de la carretera principal en la colina frente a Slivnista. A la derecha estaba un terreno montañoso escarpado mientras que el ala izquierda era de fácil acceso con las colinas Visker frente a Breznik.

Las tres divisiones centrales serbias llegaron también el día 16 de noviembre y se detuvo para recuperarse después de haber sufrido un ataque búlgaro para retrasarlos en el paso de Dragoman. La división morava se situó a cierta distancia de su objetivo, Breznik, situado al sur. El avance del norte se hallaba empantanado a lo largo del río Danubio.

The morning of November 17 came with rain and mist but not the expected Serbian attack. By 10 in the morning, Alexander ordered three battalions to advance on the right. They surprised the Danube division, who eventually rallied and pushed them back. The main Serbian attack began on the centre largely unsupported by artillery which had insufficient range. The weight of Bulgarian fire forced them back with some 1200 casualties. A relief column led by Captain Benderev recaptured the heights on the right and forced the Danube division back to the road.

At daybreak on November 18 the Serbians attacked the weaker left flank of the Bulgarian line. Just in time two battalions of the Preslav Regiment arrived to shore up the position. Further attacks in the centre were repulsed with heavy Serbian casualties and Benderev captured two further positions in the mountains.

On November 19 the Serbians concentrated two divisions for an attack on the Bulgarian left near Karnul (today Delyan, Sofia Province) in an attempt to join up with the Morava division. However, three battalions of Bulgarian troops led by Captain Popov from Sofia had held the Morava division in the Visker Hills and the flanking move failed. Alexander now ordered a counter attack which pushed the Serbians back on both flanks although nightfall prevented a complete collapse.

19-28 November

Slivnitsa was the decisive battle of the war. The Serbians fought only limited rearguard actions as they retreated and by November 24 they were back in Serbia. The Timok division in the north continued the siege of Vidin until November 29.

The main Bulgarian army crossed the border in two strong divisions (Guchev and Nikolaev), supported by flanking columns, and converged on Pirot. The Serbian army dug in on the heights west of the town. On November 27 the Bulgarian Army flanked the right of the Serbian position with Knyaz Alexander personally leading the final attack. The Serbians abandoned Pirot and fled to Niš.

El fin de la guerra y el tratado de paz

La derrota serbia hizo reaccionar a Imperio Austrohúngaro. El 28 de noviembre el embajador austrohúngaro en Belgrado, el Conde Khevenhüller-Metsch, visitó el cuartel general del ejército búlgaro y demandó el fin de las operaciones militares,amenazando que de lo contrario mobilizaría a sus tropas contra Bulgaria. El alto el fuego fue firmado el 7 de diciembre, pero no impidió que los serbios intentaran infructuosamente reconquistar Vidin con la idea de utilizarlo en negociaciones posteriores, incluso después de la demanda de alto el fuego de su aliado diplomático. El 19 de febrero de 1886 el Tratado de paz se firmó en Bucarest. Según sus términos, no hubo cambios territoriales en la frontera serbo-búlgara.

La guerra fue un paso importante en el fortalecimiento de la posición internacional de Bulgaria. En gran medida, la victoria conservaba la unificación de Bulgaria y era reconocida por las Grandes Potencias. Por parte de Serbia la derrota dejó una cicatriz permanente en el ejército serbio, considerado previamente invicto por los serbios, se iniciaron ambiciosas reformas en el ejército serbio pero el malestar latente en el ejército contribuyó al final de la Casa de Obrenović.

Referencias culturales

La Guerra Serbo-Búlgara es el escenario de la obra de George Bernard Shaw, Arms and the Man (1894)

Véase también

Wikimedia foundation. 2010.