- Rapamicina

-

Rapamicina

Rapamicina

Rapamicina

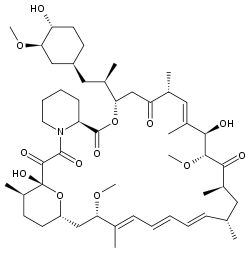

Nombre (IUPAC) sistemático (3S,6R,7E,9R,10R,12R,14S,15E,17E,19E,21S,23S,

26R,27R,34aS)-9,10,12,13,14,21,22,23,24,25,26,

27,32,33,34,34a-hexadecahidro-9,27-dihidroxi-3-

[(1R)-2-[(1S,3R,4R)-4-hidroxi-3-metoxiciclohexil]-

1-metiletil]-10,21-dimetoxi-6,8,12,14,20,26-

hexametil-23,27-epoxi-3H-pirido[2,1-c][1,4]-

oxaazaciclohentriacontina-1,5,11,28,29

(4H,6H,31H)-pentonaIdentificadores Número CAS 53123-88-9 Código ATC L04AA10 PubChem 6436030 DrugBank APRD00178 ChEBI ? Datos químicos Fórmula C37H67NO13 Peso mol. 914.172 g/mol Farmacocinética Biodisponibilidad 20%, y no comer comida rica en grasa Unión proteica 92% Metabolismo Hepático Vida media 57–63 h Excreción Mayormente fecal Consideraciones terapéuticas Cat. embarazo Estado legal Vías adm. Oral La rapamicina o Sirolimus es un antimicótico utilizado como medicamento, descubierto en Rapa Nui hace alrededor de 40 años por investigadores canadienses. Este medicamento mostró potentes propiedades antibióticas, pero en la década de los 90 también se descubrió sus propiedades de frenar la acción del sistema inmunológico y evitar el rechazo de los nuevos órganos en los casos de transplantes[1] [2] .

Tiempo después, el medicamento mostró eficacia para combatir algunos cánceres, al frenar la proliferación celular y el crecimiento de los tumores. Por esta propiedad igualmente se usa para recubrir stents medicados de uso intracoronario y prevenir su reestenosis.[3]

En julio de 2009, un artículo en la revista Nature reporta que un estudio realizado en ratones demostraba que este medicamento prolongó la vida hasta en un 38% de los sujetos del estudio,[4] hallazgo que abre expectativas sobre su uso en tratamientos para detener el envejecimiento en humanos.

Contenido

Biosíntesis

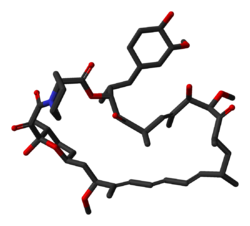

La rapamicina es un policétido macrocíclico aislado de Streptomyces hygroscopicus que ha sido mostrado como exhibiendo propiedades antimicóticas, antitumorales, e inmunosupresoras.[1] La biosíntesis de la rapamicina se acompaña con la policétido sintasa tipo I (PKS) en conjunto con la péptido no ribosomal sintetasa (NRPS). Los principales responsables de la biosíntesis de un policétido lineal, de rapamicina organizándose en tres multienzimas: RapA, RapB, RapC que contienen un total de 14 módulos (ver figura 1). Las tres multienzimas se organizan tal que el primero de cuatro módulos de cadena de policétidos elongada en RapA, las siguientes seis módulos para elongación en RapB, y el final de cuatro módulos para completar la biosíntesis del lineal policétido en RapC.[5] Then the linear polyketide is modified by the NRPS, RapP, which attaches L-pipecolate to the terminal end of the polyketide and then cyclizes the molecule yielding the unbound product, prerapamycin.[6]

Figure 1: Domain organization of PKS of Rapamycin and biosynthetic intermediates. Figure 2: Prerapamycin, unbound product of PKS and NRPS.

Figure 2: Prerapamycin, unbound product of PKS and NRPS.

The core macrocycle, prerapamycin is then modified (See figure 3) by an additional five enzymes which lead to the final product, rapamycin. First the core macrocycle is modified by RapI, SAM-dependant O-methyltransferase (MTase), which O-methylates at C39. Next, a carbonyl is installed at C9 by RapJ, a cytochrome P-450 monooxygenases (P-450). Then, RapM, another MTase, O-methylates at C16. Finally, RapN, another P-450 installs a hydroxyl at C27 immediately followed by O-methylation by Rap Q, a distinct MTase, at C27 to yield rapamycin.[7]

The biosynthetic genes responsible for rapamycin synthesis have been identified. As expected, three extremely large open reading frames (OFRs) designated as rapA, rapB and rapC encode for three extremely large and complex multienzymes, RapA, RapB, and RapC respectively.[5] The gene rapL has been established to code for a NAD+ dependant lysine cycloamidase which converts L-lysine to L-pipecolic acid (See figure 4) for incorporation at the end of the polyketide.[8] A gene rapP, which is embedded between the PKS genes and translationally coupled to rapC encodes for an additional enzyme, a NPRS responsible for incorporating L-pipecolic acid, chain termination and cyclization of prerapamycin. Additionally genes rapI, rapJ, rapM, rapN, rapO, and rapQ have been identified as coding for "tailoring" enzymes which modify the marcrcyclic core to give rapamycin (See figure 3). Finally, rapG and rapH have been identified to code for enzymes which have a positive regulatory role in the preparation of rapamycin through the control of rapamycin PKS gene expression.[9]

Figure 3: Sequence of "tailoring" steps which convert unbound prerapamycin into rapamycin.

Figure 3: Sequence of "tailoring" steps which convert unbound prerapamycin into rapamycin.

Biosynthesis of this 31-membered macrocycle begins as the loading domain is primed with the starter unit, 4,5-dihydroxocyclohex-1-ene-carboxylic acid, which is derived form the shikimate pathway.[5] Interestingly, the cyclohexane ring of the starting unit is reduced during the transfer to module 1. The staring unit is then modified by a series of Claisen condensations with malonyl or methylmalonyl substrates which are attached to an acyl carrier protein (ACP) and extend the polyketide by two carbons each. After each successive condensation, the growing polyketide is further modified according to enzymatic domains which are present to reduce and dehydrate the polyketide thereby introducing the diversity of functionalities observed in rapamycin (See figure 1). Once the linear polyketide is complete, L-pipecolic acid which is synthesized by a lysine cycloamidase from an L-lysine is added to the terminal end of the polyketide by an NRPS. Then the NSPS cyclizes the polyketide giving prerarpmycin, the first enzyme free product. The macrocyclic core is then customized by a series of post-PKS enzymes through methylations by MTases and oxidations by P-450s to yield rapamycin.

Figure 4: Proposed mechanism of lysine cyclodeaminase conversion of L-lysine to L-pipecolic acid.

Figure 4: Proposed mechanism of lysine cyclodeaminase conversion of L-lysine to L-pipecolic acid.

Referencias

- ↑ a b Vézina C, Kudelski A, Sehgal SN (octubre de 1975). «Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic.» J. Antibiot.. Vol. 28. n.º 10. pp. 721–6. PMID 1102508.

- ↑ Pritchard DI (2005). «Sourcing a chemical succession for cyclosporin from parasites and human pathogens» Drug Discovery Today. Vol. 10. n.º 10. pp. 688–691. DOI 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03395-7. PMID 15896681.

- ↑ Regara, Evelyn. Serruysa, Patrick W.El estudio RAVEL. Reestenosis del cero por ciento: ¡un sueño del cardiólogo hecho realidad. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2002;55:459-62. [1]

- ↑ Harrison, David E. et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature 460, 392-395 (16 July 2009)| doi:10.1038/nature08221.[2].

- ↑ a b c Schwecke T, Aparicio JF, Molnár I, et al. (agosto de 1995). «The biosynthetic gene cluster for the polyketide immunosuppressant rapamycin» Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.. Vol. 92. n.º 17. pp. 7839–43. PMC 41241. DOI 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7839. PMID 7644502.

- ↑ Gregory MA, Gaisser S, Lill RE, et al. (May de 2004). «Isolation and characterization of pre-rapamycin, the first macrocyclic intermediate in the biosynthesis of the immunosuppressant rapamycin by S. hygroscopicus» Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.. Vol. 43. n.º 19. pp. 2551–3. DOI 10.1002/anie.200453764. PMID 15127450.

- ↑ Gregory MA, Hong H, Lill RE, et al. (October de 2006). «Rapamycin biosynthesis: Elucidation of gene product function» Org. Biomol. Chem.. Vol. 4. n.º 19. pp. 3565–8. DOI 10.1039/b608813a. PMID 16990929.

- ↑ Graziani EI (May de 2009). «Recent advances in the chemistry, biosynthesis and pharmacology of rapamycin analogs» Nat Prod Rep. Vol. 26. n.º 5. pp. 602–9. DOI 10.1039/b804602f. PMID 19387497.

- ↑ Aparicio JF, Molnár I, Schwecke T, et al. (February de 1996). «Organization of the biosynthetic gene cluster for rapamycin in Streptomyces hygroscopicus: analysis of the enzymatic domains in the modular polyketide synthase» Gene. Vol. 169. n.º 1. pp. 9–16. DOI 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00800-4. PMID 8635756.

Bibliografía

- Diario La Tercera Sábado 29 de agosto de 2009.

Enlaces externos

Categoría: Antibióticos

Wikimedia foundation. 2010.